This entry is part of Park Views, an Asheville Parks & Recreation series that explores the history of the city’s public parks and community centers – and the mountain spirit that helped make them the unique spaces they are today. Read more from the series and follow APR on Facebook and Instagram for additional photos, upcoming events, and opportunities.

The area known as “Asheville’s front yard” has served that purpose for so long, many people may not even know that Pack Square Park is a relatively new addition to the city, officially opening under that name in 2010. However, the land that is now Pack Square Park has been the veritable heart of the city since the beginning. It’s a history that begins with indigenous footsteps and evolves into the bustling city center we know today.

From Crossroads to County Seat

From Crossroads to County Seat

Like much of modern Asheville, Pack Square Park traces its parks and recreation history to ᏣᎳᎩ, romanized as Anigiduwagi and more commonly known as the Cherokee (ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ) people, who built towns and villages throughout the area, complete with meeting plazas, hunting grounds, racetracks, and courts for ball play.

They also created trails for travel, food gathering, recreation, commerce, and many other aspects of everyday  life. All of our current-day connectivity stems from these trails – as people moved along rivers and ridgelines and through forests, trails were established. These trails turned into stagecoach routes as early European settlers moved into the area in the 1780s, then railroads in the 1880s, and finally into the complex system of roads and interstate highways we know today.

life. All of our current-day connectivity stems from these trails – as people moved along rivers and ridgelines and through forests, trails were established. These trails turned into stagecoach routes as early European settlers moved into the area in the 1780s, then railroads in the 1880s, and finally into the complex system of roads and interstate highways we know today.

After the American Revolution, Major William Davidson was granted 640 acres and built his home and a store in the Swannanoa Valley in 1787. He rode to the state capital of New Bern in 1791 with petitions from more than 1,000 people living west in the Blue Ridge Mountains asking the general assembly to form a new county to make government functions such as recording deeds more convenient. Following unanimous approval, the new county was named for plantation owner and Continental Army veteran Edward Buncombe. A committee of seven men voted to build Buncombe County’s first courthouse, prison, and stock yards on the current Pack Square site which opened in 1793.

A year later, a plan was laid out for the village, dedicating the area around the courthouse as an open space to protect it from fire. Known over the years as Court Square, Public Square, and Market Square, the area quickly became a nexus of regional commerce and government. The state legislature officially incorporated the village of Asheville in 1797, replacing the original name of Morristown with a new one in honor of North Carolina Governor Samuel Ashe.

Artery of Commerce and Growth

Artery of Commerce and Growth

While trappers and frontiersmen used Cherokee trails to navigate gorges and peaks in the mountains, they were largely insufficient for homesteaders and traders moving goods to market. As the foothills of Tennessee became major areas for raising cows, sheep, fowl, and hogs, a more efficient way to move livestock to populated coastal cities including Charleston and Augusta was needed.

Asheville’s relative isolation ended with the completion of Buncombe Turnpike in 1828. This new road linked the city to Tennessee, South Carolina, Georgia, and Kentucky, opening up a lucrative trade in livestock. Thousands of pigs  and cattle streamed directly through the square on their way to market. During this time, Asheville developed a rather rough and tumble reputation as saloons and brothels welcomed drovers with open arms.

and cattle streamed directly through the square on their way to market. During this time, Asheville developed a rather rough and tumble reputation as saloons and brothels welcomed drovers with open arms.

The arrival of the first train in 1880 launched a period of unprecedented growth as people could more easily travel and Asheville’s tourism industry began its ascent. As mayor three times during the decade when the railroad came to Asheville, Edward Aston was determined to transform Court Square from a stockyard to a community resting area with open spaces, benches, and a public water pump. During his tenure, a new courthouse on the square was completed in 1887 that included a third-story opera house with seating capacity of over 400.

In 1889, Asheville opened an electric streetcar system with cars running from the square every 15 minutes, the first of its kind in North Carolina and just second in the South. Shops, hotels, and retail establishments gradually replaced houses and livestock pens as the square firmly established itself as the commercial and social epicenter of the growing city.

Asheville built its first City Hall in 1892 on the east end of Court Square in front of what is now the Jackson Building, the same year the nearby YMI Cultural Center was commissioned in the adjacent Dicksontown neighborhood (now known as The Block). Aston’s plan to pave the streets around the square was later completed under Mayor Charles D. Blanton in 1893.

Asheville built its first City Hall in 1892 on the east end of Court Square in front of what is now the Jackson Building, the same year the nearby YMI Cultural Center was commissioned in the adjacent Dicksontown neighborhood (now known as The Block). Aston’s plan to pave the streets around the square was later completed under Mayor Charles D. Blanton in 1893.

Impact of the Pack Family

The square’s name and identity changed forever thanks to George Willis and Frances “Phoebe” Farnam Pack, philanthropists who moved to Asheville in 1884 for health reasons. George was a smart real estate speculator and developer who made multiple contributions to the future of the city due to the vast influence that came with great wealth in the growing city. Essentially retired, the Packs had time, resources, and vision.

The Packs contributed to schools, hospitals, and libraries, as well as donating land for Montford, Magnolia, and Aston parks. In 1898, Vance Monument was completed thanks in part to a large gift from George Pack. The memorial to Governor Zebulon Vance became Court Square’s signature landmark.

The Packs contributed to schools, hospitals, and libraries, as well as donating land for Montford, Magnolia, and Aston parks. In 1898, Vance Monument was completed thanks in part to a large gift from George Pack. The memorial to Governor Zebulon Vance became Court Square’s signature landmark.

The square’s most enduring change came in 1900 and would set in motion steps to transform the space into a public park. George Pack purchased a site on College Street and deeded it to Buncombe County on the condition that the courthouse move off the square. Six county courthouses had all previously been built on the square, meeting demolition as Asheville and the county continued to grow. When the seventh courthouse opened near its current location in 1903, Court Square was officially renamed Pack Square at Governor Locke Craig’s suggestion in honor of the family’s public contributions and dedicated “to the public, forever, to be used for the purposes of a public park or place.”

When the current Neo-Classical Buncombe County Courthouse opened in 1928 – on the previous site of Knickerbocker Hotel and the eighth building to bear the name – the 17-story building became the tallest local government building in the state. The current Art Deco Asheville City Hall designed by Douglas Ellington also opened in 1928, creating City-County Plaza between the two buildings on the east and Pack Square to the west.

When the current Neo-Classical Buncombe County Courthouse opened in 1928 – on the previous site of Knickerbocker Hotel and the eighth building to bear the name – the 17-story building became the tallest local government building in the state. The current Art Deco Asheville City Hall designed by Douglas Ellington also opened in 1928, creating City-County Plaza between the two buildings on the east and Pack Square to the west.

The Municipal Building opened on the site of the previous City Hall housing the city’s police and fire departments with cornucopias over the side doorway marking the entrance to basement-level City Market, located there until 1932. A planned 5,000-seat auditorium was never built, but the idea to build a performing arts center near the square has circulated in the 100 years since. James Vester Miller was the chief brick mason for the building and an Urban Trail station is placed in honor to him and all of the African-American craftsmen who helped build the city. The building remains home to fire and police headquarters.

A Century of Social Life

A Century of Social Life

The early 20th century saw a dramatic construction boom that physically reshaped downtown Asheville. By the late 1920s, Pack Square was framed by new architectural landmarks, shops, and boarding houses and hotels. Despite a long period of financial difficulty for the city following the Great Depression, Pack Square remained the heart of social activity, hosting everything from holiday parades and musical performances to ceremonies welcoming soldiers home from war and rallies.

Even as the square evolved with new buildings, including the Northwestern Bank building in 1965 (now The Arras, Asheville’s tallest building) and the iconic I.M. Pei-designed Akzona Building in 1980, the area was always a gathering point. Events like Shindig on the Green, Bele Chere, Goombay, Downtown After 5, First Night, and other festivals kept Pack Square and City-County Plaza vital through the 1970s, 1980s, and into the new millennium. Though individual parcels of land are owned by county and city governments, the City of Asheville has long been in charge of maintenance and event permits.

The original plan for the Akzona Building (now the Biltmore Building) included razing all buildings on Pack Square, but Preservation Society of Asheville and Buncombe County negotiated the preservation of buildings on South Pack Square. The transformation led to the City of Asheville-funded Pack Square Rehabilitation Project and included burial of above-ground utility wires, street paving, landscaping, pool and fountain construction, and changes to traffic and parking patterns. Changes to Pack Square coincided with a new era of civic pride – or mountain spirit, as it’s often called in Asheville.

The original plan for the Akzona Building (now the Biltmore Building) included razing all buildings on Pack Square, but Preservation Society of Asheville and Buncombe County negotiated the preservation of buildings on South Pack Square. The transformation led to the City of Asheville-funded Pack Square Rehabilitation Project and included burial of above-ground utility wires, street paving, landscaping, pool and fountain construction, and changes to traffic and parking patterns. Changes to Pack Square coincided with a new era of civic pride – or mountain spirit, as it’s often called in Asheville.

In the 1980s, the buildings on South Pack Square were renovated, and Pack Place Arts, Education, and Science Center opened in 1992 on the site of the original Pack Memorial Library (which moved to its current location in 1978) and Plaza Theater. Pack Place brought together Asheville Art Museum, Colburn Gem & Mineral Museum (now Asheville Museum of Science), The Health Adventure, YMI Cultural Center, and the City of Asheville Historic Resources Commission, along with new performance hall Diana Wortham Theatre (now Wortham Center for the Performing Arts), to create a cultural center anchored in Pack Square and designed to spark the city’s revitalization. The center housed a permanent exhibit about the square’s colorful history, Three Centuries in Pack Square. The Health Adventure and Colburn Gem & Mineral Museum later moved out of Pack Place to allow for the art museum’s expansion.

A Vision Complete

A Vision Complete

When a leak in the square’s fountain created a street-level sinkhole in 1999, it prompted downtown supporters to form the Pack Square Renaissance task force. Its vision to realize the Pack family’s century-old dream launched a complex process of planning, design, and fundraising.

In 2000, the nonprofit Pack Square Conservancy was established to oversee the creation and funding of a unified park on the 6.5 acres of public land that included Pack Square and City-County Plaza. The City of Asheville and Buncombe County were the first donors to the project with contributions of $7,500 each. Other early funds came from a $4 million federal grant and $2 million from the Buncombe County Tourism Development Authority’s Tourism Product Development Fund. Despite the strong start, the Conservancy dissolved just a few years later following the park’s opening citing a challenging environment for fundraising following the Great Recession.

The public groundbreaking for Pack Square Park was celebrated on August 18, 2005, and construction began on September 22, but experienced early complications including extreme weather and underground surprises such as areas of asphalt paving and heavily reinforced concrete measuring a yard thick. Construction material cost increases and project delays escalated the budget, but primary park infrastructure including laying nearly 10,000 bricks was completed in 2007 and the Conservancy put its focus on the major features of the park.

The public groundbreaking for Pack Square Park was celebrated on August 18, 2005, and construction began on September 22, but experienced early complications including extreme weather and underground surprises such as areas of asphalt paving and heavily reinforced concrete measuring a yard thick. Construction material cost increases and project delays escalated the budget, but primary park infrastructure including laying nearly 10,000 bricks was completed in 2007 and the Conservancy put its focus on the major features of the park.

After years of construction and extensive public input, sections of Pack Square Park began to welcome the public in 2009 with a grand opening on May 28, 2010. The three sections of the park include J. Rush Oates Plaza with a four-ton bronze and stone fountain designed by Asheville sculptor Hoss Haley, Rueter Terrace, and Roger McGuire Green with the popular Spasheville splashpad, WNC Veterans Memorial, amphitheater seating, and Bascom Lamar Lunsford Stage featuring a stainless steel pergola funded by Asheville Downtown Association and hundreds of colorful tiles made by middle school students and local ceramicist Kathy Triplett.

The park quickly became an intersection for troubadours, festivals, performances, family gatherings, and community members connecting with nature in the heart of downtown. With 11 pieces of the City of Asheville’s public art collection (including seven Urban Trail stations), multiple monuments at Buncombe County Courthouse, and one of the last remaining phone booths in the city scattered among native trees and plants, Pack Square Park is a beautiful, modern green space that honors its past as a native crossroads, county seat, and commercial hub. It continues as the central stage for life in Asheville, a permanent public park for generations of residents and visitors.

Proving that continual reinvention is an Asheville trademark, a grant from the Mellon Foundation’s Monuments Project seeks an updated community vision for a more accessible and inclusive Pack Square Plaza. A vision plan was unanimously adopted by City Council in 2023.

Do you have photos or stories to share about Pack Square Park? Please send them to cbubenik@ashevillenc.gov so APR can be inspired by the past as we plan our future.

Photo and Image Credits

- A poster of a 1987 original painting by Judith Cheney includes many of the businesses and events prominent during that era with ample Easter eggs for Ashevillains who called the city home at the time. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

- One of multiple Urban Trail stations in the park, Crossroads stands on the bed of a road that was once traveled by Native Americans and later by drovers who herded livestock across the mountains from Tennessee to southern markets, taking turkeys, pigs, and cows as far as Charleston and Savannah. Embedded rails from former Asheville trolley trails represent the coming of the train in 1880 and electric streetcars in 1889, opening the door to growth along Patton Avenue. While the animal prints show them walking north, they would almost certainly be traveling the other direction.

- What are now Biltmore Avenue and Broadway Street used to be North Main and South Main streets until 1914. This gentleman sits in an ox-drawn wagon near the square on the corner of Eagle Street and South Main drinking from an earthen jug in front of White Man’s Bar in the late-19th century. Asheville’s status as a livestock town was matched by its reputation for rowdiness and boisterous activity. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

- This image published by Nat. W. Taylor looking down Patton Avenue from the courthouse in 1883 shows an early attempt to create a public park space on the square with fencing, benches, gas lamp posts, and planted grass, as well as an area to hitch and water horses. The square’s first fountain water feature was installed in this area in 1885. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

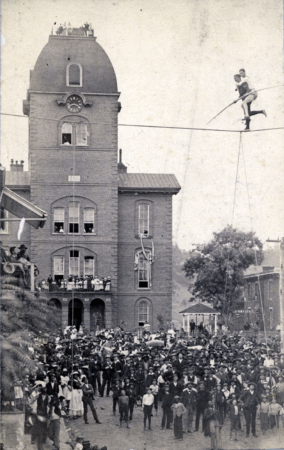

- A large crowd gathered to watch two men on a high wire in front of the Buncombe County Courthouse, circa 1887. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

- Traffic jam? A photo from 1890 looking north shows horse-drawn wagons and electric streetcars. They would soon be joined by a growing use of “safety bicycles” and automobiles. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

- George Willis Pack was originally from New York, but found success in Michigan’s lumber industry. He and his wife moved to Asheville in 1884 for health reasons. Essentially retired, he had time and resources to contribute to what Asheville would soon become. Portrait of George Willis Pack (1831-1906) donated by R.J. Stokely. Portrait of Frances “Phoebe” Farman Pack (1834?-1917) photo copied by Edmondson (Cleveland, Ohio). Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

- With 14,694 inhabitants in 1900, Asheville was the third largest city in North Carolina and would grow to 50,000 by 1930. This 1910 scene of the square captures a transformational period for the city with trolley cars, automobiles, and horse-drawn carts, as well as several community members. The Palmetto Building on the right was built in 1887 for the First National Bank, joining together two smaller buildings that had been on the square since before the Civil War and adding a stucco exterior for a castle-inspired effect. The building was the home of Pack Memorial Library from 1899-1925. To the left of the Palmetto Building is the Legal Building, built in 1909. The 1892 City Hall is in the center and housed City Market, Asheville Fire Department, and government offices. The dome of the 1903 Buncombe County Courthouse can be seen behind City Hall. The image was digitally enhanced by Mark Combs in 2009 and colorized by Melanie Arrowood in 2020. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

- Personal automobiles and public transportation were integrated into everyday life by the mid-20th century. Buncombe County Courthouse and City Hall relocated to the east, creating City-Council Plaza with public greenspace that was dissected by a number of streets and parking spaces. This is one of the only times that a water feature has not been located on the square since 1865, though the entrance to restrooms located underground is visible near the parked bus in the foreground. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

- A view of the 1934 Rhododendron Festival parade showed that Asheville could celebrate through hard times. Asheville Holiday Parade, the city’s largest remaining parade, utilizes a route that passes through the square. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

- George and Phoebe Pack’s great-granddaughter Elizabeth Boggs spoke at the opening of Pack Place on July 4, 1992 with the Akzona Building in the background in this photo by Deborah Compton. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

- One of the final years of City-Council Plaza and Pack Square shows a space made for vehicles with green space serving a secondary function. The stage near the center was set up for Shindig on the Green. A diagonal street cut through the middle section of the current park creating an isolated triangular island between College, Spruce, and South Market streets that was long home to Energy Loop, the city’s first piece of public art.

- Construction took longer than expected. Coupled with rising costs and fundraising challenges, a planned $2 million endowment to cover park maintenance in perpetuity never materialized and Asheville Parks & Recreation has maintained the park since Pack Square Conservancy’s disillusionment shortly after Pack Square Park opened.

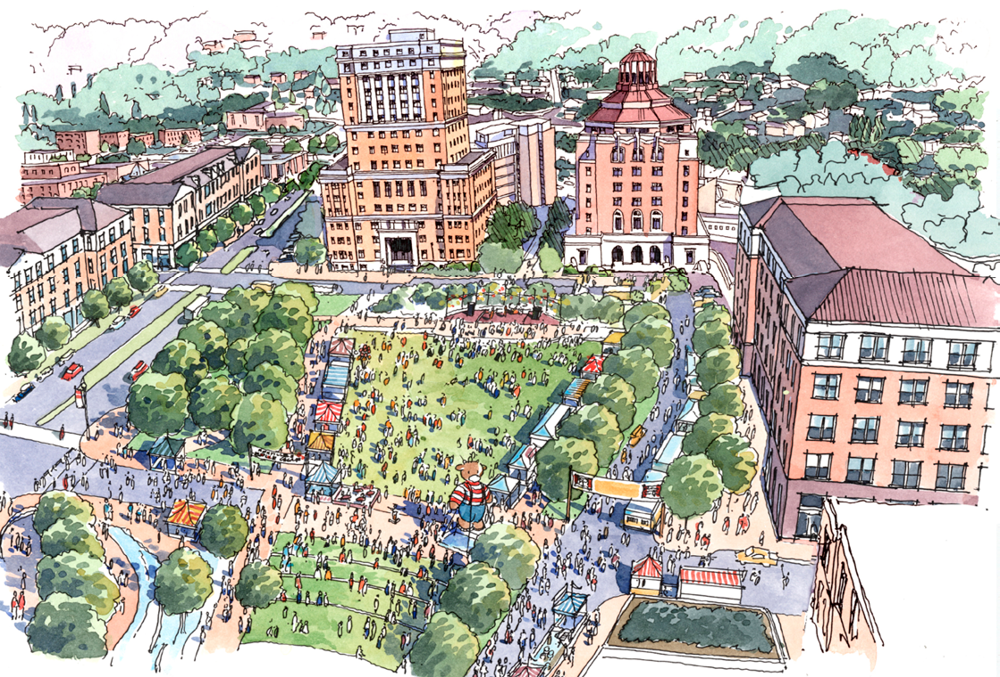

- A concept sketch of Reuter Terrace and Roger McGuire Green display plans for a space for friends, neighbors, and community members to connect with each other and celebrate the shared experience of living in a great city.