Asheville Parks & Recreation (APR) manages a unique and evolving collection of parks, playgrounds, and open spaces throughout the city in a system that also includes full-complex recreation centers, swimming pools, greenways, sports fields and courts, resting areas, and community centers that offer a variety of programs for Ashevillians of all ages. However, many newcomers and longtime community members may not know the stories behind these public spaces. Over the course of 2023, the Park Views blog series will explore that history by highlighting a different park each Thursday.

Togiyasdi

For thousands of years, the Cherokee built towns and villages, complete with defensive palisades and plazas for ball play, along the Swannanoa and French Broad rivers. They called the river confluence ᏙᎩᏯᏍᏗ (Togiyasdi, “the place where they race”) and also used the area for open meeting and hunting grounds.

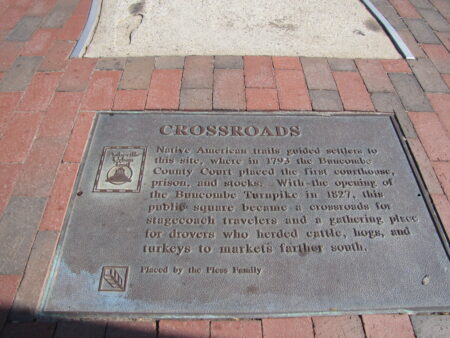

They also created trails used for travel, food gathering, recreation, commerce, and many other aspects of everyday life. All of our current-day connectivity stems from these trails – as people moved along rivers and ridgelines, and through forests, trails were established. These trails turned into stagecoach routes, then railroads, and finally into the complex system of roads and interstate highways we know today.

Boom to Bust

Boom to Bust

From at least 1797, the area in and around Pack Square Park has acted as the city’s public square, providing many of the benefits of present-day parks. The arrival of rail service in 1880 transformed the livestock town into a resort destination and center of commerce and healthcare for the region. Asheville’s modern public parks began to take shape in the 1890s when George Willis Pack provided land for Aston and Montford parks.

With 14,694 inhabitants in 1900, Asheville was the third largest city in North Carolina and would grow to 50,000 by 1930. During this short-lived, rapid growth spurt, a city of parks, plazas, and parkways was envisioned in John Nolan’s city plan. A spending spree brought an unprecedented number of publicly-funded projects including Recreation Park, Asheville Municipal Golf Course, McCormick Field, Memorial Stadium, and several others.

However, this epic boom ended in a cataclysmic bust. In 1930, local banks failed, saddling Asheville with $41 million in debt – more than the debts of Raleigh, Durham, Greensboro, and Winston Salem combined. To prevent further liabilities, no new debts could be incurred unless they were approved by a majority of voters in a referendum. For this reason, the park system remained largely stagnant for the following decades.

Asheville Parks & Recreation Begins

Asheville Parks & Recreation Begins

APR began providing recreation services in 1933 as the parks and playgrounds division under the direction of City of Asheville Public Works. In 1945, a year-round recreation program was instituted to manage APR’s ten parks and a full-time administrator was hired.

The first APR director was named in 1956. During her tenure, new community centers and parks were developed, as well as accompanying programs for children, teens, and older adults. While she was successful in improving recreation programs, she did not have the luxury of quality facilities and the department was forced to use schools and other community organizations’ buildings to house activities during much of this time.

A Growing System

A Growing System

In 1971, the department’s new director asked City Council to double the department’s small annual budget, paired it with grants, and leveraged an abundant amount of federal money to embark on a period of sizable expansion.

During public school desegregation, most of Asheville’s schools for Black students were closed as those students transferred to previously all-white schools. Many of the shuttered school buildings were adapted into recreation and cultural arts centers. APR After School grew out of this focus in the 1980s.

Some large-scale facilities opened over the next 20 years including Montford Recreation Complex and Riverside Park (now collectively known as Tempie Avery Montford Community Center) and Martin Luther King Jr. Park. Asheville’s long-running Bele Chere festival began during this time and would be hosted by APR each summer for 35 years.

Entering the Twenty-First Century

Entering the Twenty-First Century

In 1994, APR became the first nationally-accredited municipal recreation department in the United States and began the process of developing the community’s first long-range comprehensive parks and recreation master plan, leading to an $18 million public bond referendum vote in 1999 to fund improvements. It ultimately failed by just 357 votes, but brought public attention to the lack of resources for the aging system. APR won National Recreation and Park Association’s Gold Medal Award in 2002 as a testament to the department’s creativity and resourcefulness.

Major projects including Azalea Park, Carrier Park, French Broad River Park, and Richmond Hill Park significantly increased park acreage within city limits. In 2005, Asheville Municipal Golf Course, Aston Park Tennis Center, McCormick Field, Recreation Park, and WNC Nature Center once again became part of the APR system following 20 years of management by Buncombe County.

With significant interest in expanding greenways, public art, and cultural programs, the community updated the parks and recreation master plan in 2009. This led to another bond referendum vote in 2016 to address deferred maintenance, add major enhancements, and acquire land for investments throughout the city. 77 percent of voters approved the bond.

While APR’s portfolio and offerings have changed over the decades, it remains focused on locally-driven innovative solutions to equity, funding, and sustainability through parks and recreation. In 2023, the department will begin the process of updating the city’s parks and recreation master plan to prepare for the years ahead.

Share Your Stories

There’s only so much to be gleaned from historic documents, city plans, and newspaper articles. History and memories continue to be made in Asheville’s parks and facilities every day. If you’ve got photos or narratives to share, please send them to cbubenik@ashevillenc.gov.

Follow us on Facebook and Instagram for additional photos, upcoming events, and opportunities.

Photo and Image Credits

-

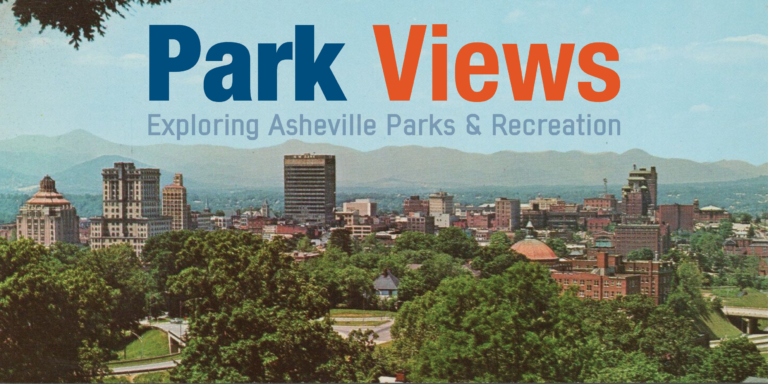

‘Asheville, North Carolina seen from Beaucatcher Mountain. Photographed in Natural Color by Jack Bowers’ from W.M. Cline Co.

-

Asheville Urban Trail markers relate a condensed history of the area through public art and bronze markers throughout downtown

-

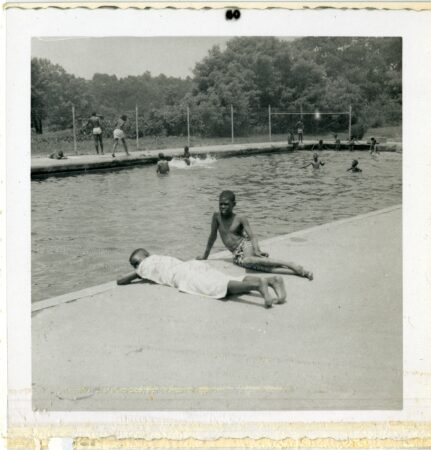

Young men at Walton Street Pool, courtesy of Isaiah Rice Photography Collection, University of North Carolina Asheville Special Collections

-

Haywood Street during the first Bele Chere festival in 1979, courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina

-

APR team members during a staff retreat in 2022

Boom to Bust

Boom to Bust Asheville Parks & Recreation Begins

Asheville Parks & Recreation Begins A Growing System

A Growing System Entering the Twenty-First Century

Entering the Twenty-First Century