This entry is part of Park Views, a weekly Asheville Parks & Recreation series that explores the history of the city’s public parks and community centers – and the mountain spirit that helped make them the unique spaces they are today. Read more from the series and follow APR on Facebook and Instagram for additional photos, upcoming events, and opportunities.

When Walton Street Park opened in 1939, many of Asheville’s Black residents could safely walk to a playground, picnic areas, tennis courts, and green space for celebrations and meetings within minutes of their homes for the first time. While the neighborhood that surrounds it has changed dramatically since then, the park layout remains relatively unaltered and offers a glimpse into the lasting power of community.

Funding a Park

While Aston and Montford parks date back to the 1890s, public recreation opportunities for Black families primarily consisted of small neighborhood playgrounds, spaces at schools such as gymnasiums, and open field lots throughout the era of government-mandated segregation. In 1916, the City of Asheville spent $5,000 to both enlarge the whites-only pool in Aston Park and build another for Black residents next to Mountain Street School in the East End neighborhood, marking the City’s first significant investment in public recreation for African American residents.

While Aston and Montford parks date back to the 1890s, public recreation opportunities for Black families primarily consisted of small neighborhood playgrounds, spaces at schools such as gymnasiums, and open field lots throughout the era of government-mandated segregation. In 1916, the City of Asheville spent $5,000 to both enlarge the whites-only pool in Aston Park and build another for Black residents next to Mountain Street School in the East End neighborhood, marking the City’s first significant investment in public recreation for African American residents.

Mountain Street Pool was popular – and overcrowded – from the time it opened until it closed in the mid-1930s. Other recreation programs for the city’s African American citizens were organized from Valley Street Community Center and included playgrounds adjacent to Burton Street, Mountain Street, Livingston Street, Hill Street, and other Black schools.

Still reeling from local bank failures in 1930, the City of Asheville funded few parks and recreation investments until the WPA offered federal money to carry out public works projects. In their 1935 applications for these government funds, the City included plans for an as-yet-to-be-located park for African Americans. A 22-acre tract called Campbell’s Woods, located behind Hill Street School (location of today’s Isaac Dickson Elementary School), was purchased with plans to develop a playground, pool, community center, and sports fields. However, Montford residents successfully protested it would threaten their property values and was not centrally located to serve Black community members.

Riverview Park

In January 1938, the location of the new park was officially chosen on the southern edge of East Riverside, the neighborhood known today as Southside. It opened as Riverview Park on June 3, 1939 with speeches from elected officials and church leaders and music from the Stephens-Lee High School band. Its features included tennis courts, horseshoe pits, and a wading pool with hopes a full sized swimming pool would open by the next summer. Joining supervised summer playground programs at Magnolia Park, Mountain Street School, Gudger Street playground, and Southside athletic field, the park offered daily activities for Black children.

In January 1938, the location of the new park was officially chosen on the southern edge of East Riverside, the neighborhood known today as Southside. It opened as Riverview Park on June 3, 1939 with speeches from elected officials and church leaders and music from the Stephens-Lee High School band. Its features included tennis courts, horseshoe pits, and a wading pool with hopes a full sized swimming pool would open by the next summer. Joining supervised summer playground programs at Magnolia Park, Mountain Street School, Gudger Street playground, and Southside athletic field, the park offered daily activities for Black children.

Along with the YMI, Riverview Park was the primary location of the city’s annual Rhododendron Festival events for African Americans. Parades, concerts, picnics, card and game tournaments, and tennis, horseshoe, and shuffleboard competitions separate from the festival’s events for the white population took place at the park. It remained popular for many other community events, as well as daily life, but momentum to add a pool was slowed when the U.S. entered World War II.

By 1944, 1,255 Black children were served through the summer playground program at Hill Street School and Riverview, Southside, Eagle Street, and West Asheville parks. Asheville Parks & Recreation (APR), then a division of Public Works, also hosted games, sports, dramatics, arts and education classes, reading rooms, meeting places, and a nursery school for Black kids, teens, adults, and veterans out of Valley Street Community Center. However, the funding of a much-needed replacement for Mountain Street Pool dragged on so long that both white and Black community members advocated to City Council to finance the project.

Walton Street Pool

Although officially listed as Riverview Park on APR documents into the 1960s, it had become more commonly referred to as Walton Street Park by 1947, the year $22,500 was budgeted for a pool and improved landscaping. Though some campaigned for the pool to be located in Campbell’s Woods, East End, or a pine knoll off of McDowell Street, Walton Street Pool officially opened on July 5, 1948. Four young men from the neighborhood received lifeguard certification (and presumably supervised the site) before the pool closed in early August due to polio restrictions.

Although officially listed as Riverview Park on APR documents into the 1960s, it had become more commonly referred to as Walton Street Park by 1947, the year $22,500 was budgeted for a pool and improved landscaping. Though some campaigned for the pool to be located in Campbell’s Woods, East End, or a pine knoll off of McDowell Street, Walton Street Pool officially opened on July 5, 1948. Four young men from the neighborhood received lifeguard certification (and presumably supervised the site) before the pool closed in early August due to polio restrictions.

A bathhouse opened the following summer. An earlier bathhouse was constructed, but burned along with a pavilion shortly after the park opened and was not rebuilt. The popularity of the pool led to the expansion of other park facilities: new picnic tables, refurbished tennis courts, new horseshoe pits, and fireplaces in the picnic area. Walton Street Park became home to the city’s third public pool with the other two designated for white community members. Like Walton Street Pool, Malvern Hills Pool was free. The much larger Recreation Park Pool charged a fee.

Walton Street Park remained the only public recreation area of its kind serving the city’s 15,000 Black residents through much of the next decade. No schools or public spaces designated for them had dedicated space for football, baseball and softball, track, or lighted outdoor gatherings until a softball diamond was added to the park in the mid-1950s. Petitions and requests to expand Walton Street Park, develop the long-discussed recreation complex at Campbell’s Woods, or add a park near Burton Street School gained traction, but no results.

Asheville Municipal Golf Course had already become the first publicly-owned golf course in the state to be racially integrated, allowing African American community members to play on Mondays and Tuesdays. Following the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision on Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 and subsequent public parks rulings, the golf course and Asheville’s parks, community centers, and pools were no longer officially associated with individual races.

In spite of this, swimming pools at Malvern Hills and Walton Street parks continued to essentially operate for white and Black clientele, respectively. (Recreation Park’s pool closed in 1956 and a new one wouldn’t open until 1970.) Similarly, separate July 4 fireworks displays took place at Recreation and Walton Street parks. An annual APR tennis tournament for Black players continued to be hosted proudly on Walton Street’s courts into the 1960s.

East Riverside Redevelopment

Alongside civil rights gains in the 1960s, Southside became the site of Asheville’s second large-scale urban renewal project and ultimately the largest such project in the southeast, demolishing houses considered substandard, regrading lots, widening and extending streets and sidewalks, and adding parks with the stated goal to transform the neighborhood into a more suburban and residential area. Parks on Livingston and Choctaw streets were created along the Nasty Branch stream’s route by removing beauty parlors, barber shops, gas stations, funeral homes, doctor’s offices, and other businesses that comprised the neighborhood’s commercial center.

Alongside civil rights gains in the 1960s, Southside became the site of Asheville’s second large-scale urban renewal project and ultimately the largest such project in the southeast, demolishing houses considered substandard, regrading lots, widening and extending streets and sidewalks, and adding parks with the stated goal to transform the neighborhood into a more suburban and residential area. Parks on Livingston and Choctaw streets were created along the Nasty Branch stream’s route by removing beauty parlors, barber shops, gas stations, funeral homes, doctor’s offices, and other businesses that comprised the neighborhood’s commercial center.

An area that had been considered for a five to ten acre expansion of Walton Street Park became apartments. The park and pool remained an important hub of the neighborhood with sports, picnics, and swimming key to connecting residents whose homes survived urban renewal and those in newly established public housing. A basketball court was added in the 1960s.

As federal programs transformed Southside, they were also financing new parks and improving existing recreation facilities in other parts of the city. When Walton Street Park users brought attention to poor conditions of the park’s amenities following vandalization, APR invested $80,000 to renovate the pool and bathhouse, refurbish the courts, and regrade and replace lighting at the ballfield. The playground was expanded with new equipment in 1976 and a new picnic shelter added in 1979.

Tennis courts were removed and regraded by 1985, possibly due to the availability of newer courts nearby at Livingston and Choctaw parks.

Lasting Legacy

In 1986, City Councilor Wilhelmina Bratton invited her fellow council members to a brown bag lunch at Walton Street Park to see first-hand the diminishing conditions of the park and pool, resulting in pool renovations four years later. APR and the community continued to host concerts, summer camps, and other events in the park, but as many of Southside’s founding families moved from the area or passed away, a public campaign to document and honor the site’s significance gained traction.

In 1986, City Councilor Wilhelmina Bratton invited her fellow council members to a brown bag lunch at Walton Street Park to see first-hand the diminishing conditions of the park and pool, resulting in pool renovations four years later. APR and the community continued to host concerts, summer camps, and other events in the park, but as many of Southside’s founding families moved from the area or passed away, a public campaign to document and honor the site’s significance gained traction.

Rumors emerged that the park and pool would be replaced by a street leading into AB Tech’s campus, arguing it would ease daily congestion and enhance safety in the event of an emergency campus evacuation. As many artifacts of 20th century Black life in Asheville have been demolished, the community responded to Southside neighbor’s voices and the street was not built.

Following multiple years of patches and repairs, a 2016 professional evaluation of the pool found its infrastructure inadequate with major leaks and failing underground pipes, recommending replacement rather than renovation. Walton Street Pool has been closed since the summer of 2021. That summer, APR contracted with YWCA of Asheville for Southside residents to use their pool at no charge, in addition to offering free bus rides to pools at Malvern Hills and Recreation parks. In 2022, the department hosted multiple Walton Street Water Days in the park with free water-based activities closer to Southside homes.

Recognizing the importance of services like swim lessons for kids and water aerobics for older adults, City Council approved building a new pool about a quarter of a mile from the park at Dr. Wesley Grant Sr. Southside Community Center. To preserve the original pool’s legacy as a symbol of African American culture, Walton Street Park has been designated as a local historic landmark.

Balancing the historical significance of Walton Street Park and the importance of modern, high-quality recreational spaces in Southside, APR has allocated $500,000 to implement neighborhood-guided improvements. As advocates pursue listing the park and pool on the National Register of Historic Places, a number of ideas for adaptive reuse of the pool have been suggested.

Check out the Walton Street Park Landmark Designation Report for a more detailed look at its history. For more on Southside and Black roots in Asheville, read the Asheville African American Heritage Resource Survey.

Do you have photos or stories to share about Walton Street Park? Please send them to cbubenik@ashevillenc.gov so APR can be inspired by the past as we plan our future.

Photo and Image Credits

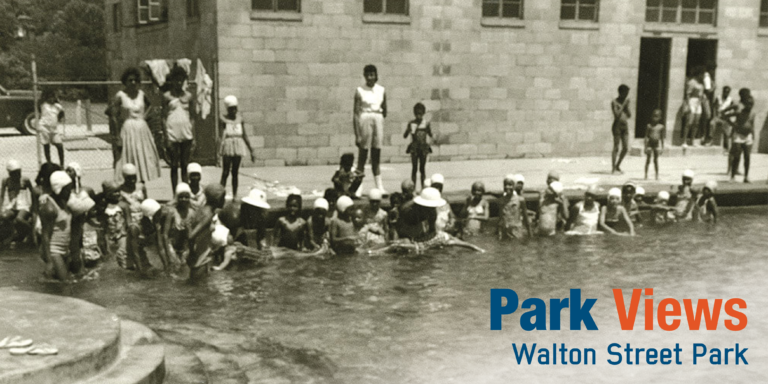

- A typical scene from the pool’s early days. Courtesy of Asheville YMCA Archives, University of North Carolina Asheville Special Collections.

- During Asheville’s short-lived, rapid growth spurt of the early 20th century, John Nolen’s plan adopted by the City of Asheville envisioned many parks, plazas, and parkways. Among the proposed segregated parks were two for Asheville’s Black community, Victoria Park in Southside and Washington Park near Hill Street School. When funding was eventually secured to build a park for the Black population, these locations were the two most frequently mentioned. While Walton Street Park is just north of the proposed Victoria Park site, several Black leaders protested its less-central location and proximity to railroad tracks. John Nolen and Philip W. Foster, City Planning Report: Asheville, North Carolina, Cambridge, MA: Harvard Square, 1922.

- Tennis was a major draw for the park’s first 40 years. Cecil Holt (pictured with his father, Washington) learned how to play tennis in the first grade when Rev. R.L. Jones of Hopkins Chapel Church convinced the City of Asheville to clear property behind the church and build a clay tennis court next to the cemetery. He won APR tournaments at Walton Street Park in 1950 and 1952, remarking, “This gave me the self-confidence needed to be a winner.” He earned a scholarship to Tillostson College in Texas where he became the Southwest Champion in doubles and won 16 trophies. Excerpt from The Greatest Sports Heroes of the Stephens-Lee Bears by Johnny Bailey and Benny Lake, Alexander Books, 2006.

- This photo from the 1950s shows Walton Street Pool as the center of summer fun. Isaiah Rice, an Asheville native, worked for the WPA during the Great Depression, served in the U.S. Army, and supervised recreation programs at Burton Street School. His photographs of Black life in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s help preserve the history, art, community, vivid personalities, and resiliency of African Americans in Asheville. Courtesy of Isaiah Rice Photograph Collection, University of North Carolina Asheville Special Collections.

- An aerial view of Walton Street Park in 1974 includes the pool and bathhouse, basketball court, lighted ballfield and tennis courts, and picnic areas. According to the Walton Street Park Landmark Designation Report, the simultaneous forces of urban renewal and integration disrupted almost all of the physical and institutional foundations of Black life in Asheville. Urban renewal radically transformed the landscape of Southside by adding apartments like those to the west of the park and regrading Livingston and Depot streets, extending Livingston Street to meet Depot Street, removing the southern portion of Southside Avenue, and eliminating Herrman, Beech, Black, Tiernan, and Nelson streets. Courtesy of Housing Authority Corporation of Asheville Archives, University of North Carolina Asheville Special Collections.

- While investments at Walton Street Park, Herb Watts Park, and Grant Southside Center bring long-requested recreation amenities to the neighborhood, events like Walton Street Water Days prove old-fashioned fun and community block parties never go out of style.