Asheville Parks & Recreation manages a unique collection of more than 55 public parks, playgrounds, and open spaces throughout the city in a system that also includes full-complex recreation centers, swimming pools, Riverside Cemetery, sports fields and courts, and community centers that offer programs related to wellness, education, and culture for Ashevillians of all ages.

While many of these beautiful places are named after the neighborhoods in which they’re located, some are named after prominent local figures who helped shape our city. In honor of Black Legacy Month, take a few minutes to learn the significance behind the names of some of Asheville’s community centers.

Tempie Avery Montford Community Center

Tempie Avery was a young girl purchased in Charleston in 1840 by Nicholas Woodfin. During her time on his plantation, she became a midwife delivering both Black and white babies in Asheville. After the Civil War, Woodfin deeded an acre of land on Pearson Drive to Avery. Prior to the expansion of Montford beyond West Chestnut Street, the area adjacent to Avery’s property was a thriving Black neighborhood known as Stumptown. While her life after emancipation was not easy, the widow used her skills as a nurse and midwife to support herself and her children.

Tempie Avery was a young girl purchased in Charleston in 1840 by Nicholas Woodfin. During her time on his plantation, she became a midwife delivering both Black and white babies in Asheville. After the Civil War, Woodfin deeded an acre of land on Pearson Drive to Avery. Prior to the expansion of Montford beyond West Chestnut Street, the area adjacent to Avery’s property was a thriving Black neighborhood known as Stumptown. While her life after emancipation was not easy, the widow used her skills as a nurse and midwife to support herself and her children.

When it opened in 1974, Montford Recreation Center was only the first ever facility built by Asheville Parks & Recreation designed exclusively for recreational and cultural programming (rather than converting an existing building). In 2017, Asheville City Council unanimously approved a resolution to rename the center to Tempie Avery Montford Community Center. A series of bond-funded improvements were completed in 2019.

Burton Street Community Center

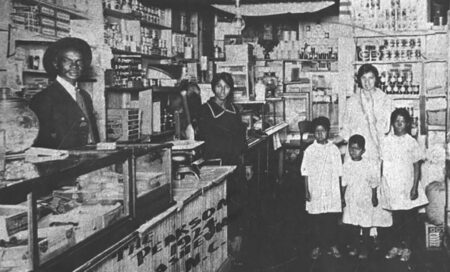

Former U.S. Army Buffalo Soldier Edward Walton Pearson Sr. began developing the Burton Street (then known as Pearson Park) and Park View subdivisions in 1906. In addition to selling real estate, Pearson was known as the “Black Mayor of West Asheville” and operated several businesses in the neighborhood including a general store, Mountain City Mutual Insurance Company, and a mail order shoe business called Piedmont Shoe Company. His vision to improve the quality of life for the city’s Black residents included organizing the Asheville Royal Giants semi-pro baseball team, establishing North Carolina’s first chapter of the NAACP, and founding the area’s first regional agricultural fair.

Former U.S. Army Buffalo Soldier Edward Walton Pearson Sr. began developing the Burton Street (then known as Pearson Park) and Park View subdivisions in 1906. In addition to selling real estate, Pearson was known as the “Black Mayor of West Asheville” and operated several businesses in the neighborhood including a general store, Mountain City Mutual Insurance Company, and a mail order shoe business called Piedmont Shoe Company. His vision to improve the quality of life for the city’s Black residents included organizing the Asheville Royal Giants semi-pro baseball team, establishing North Carolina’s first chapter of the NAACP, and founding the area’s first regional agricultural fair.

Burton Street School (originally Buffalo Street School) opened in 1916 as a two-room building to serve West Asheville’s Black families. A second building was erected in 1928 to accommodate more students and consisted of four classrooms, auditorium, lunch room, library, and offices. Following the integration of Asheville City Schools, the building became Burton Street Community Center. Painted on the west side of the center, a mural of E.W. Pearson stands watch over the neighborhood he shaped more than 100 years ago.

Burton Street School (originally Buffalo Street School) opened in 1916 as a two-room building to serve West Asheville’s Black families. A second building was erected in 1928 to accommodate more students and consisted of four classrooms, auditorium, lunch room, library, and offices. Following the integration of Asheville City Schools, the building became Burton Street Community Center. Painted on the west side of the center, a mural of E.W. Pearson stands watch over the neighborhood he shaped more than 100 years ago.

Linwood Crump Shiloh Community Center

The Shiloh community began as a small group of distant relatives in an area north of where Biltmore is located today. When George Vanderbilt bought the land for his mountain home, the entire community – including Shiloh Church and the church cemetery – moved to its current location.

In 1927, a new six-room school was built to replace a building that burned a few years prior. An addition was added in 1950 and Shiloh graduated its last class in 1969 following integration of city schools. As a community center, the building continues to act as the heart of the neighborhood. In 2006, Asheville City Council renamed the complex Linwood Crump Shiloh Community Center after a long-time community activist who lived in Shiloh for more than 50 years. Known for his advocacy of neighborhood improvements and interest in the welfare of children, Crump coached hundreds of neighborhood kids in baseball, football, and basketball. Much of his work and volunteer time was spent at the community center until he passed in 2005.

Dr. Wesley Grant, Sr. Southside Community Center

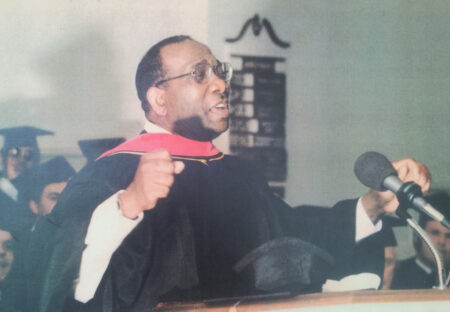

Asheville Parks & Recreation’s newest neighborhood community center opened in 2010 and was named for a prominent leader during the civil rights movement and period of urban renewal in the 1960s and 1970s. Dr. Wesley Grant, Sr., founded the Worldwide Missionary Tabernacle Church in 1959 and served there for nearly 50 years. Born in South Carolina, Grant lived in Asheville for 75 years and worked to achieve strides such as the election of Ruben Daley as the first Black member of Asheville City Council in 1969.

Asheville Parks & Recreation’s newest neighborhood community center opened in 2010 and was named for a prominent leader during the civil rights movement and period of urban renewal in the 1960s and 1970s. Dr. Wesley Grant, Sr., founded the Worldwide Missionary Tabernacle Church in 1959 and served there for nearly 50 years. Born in South Carolina, Grant lived in Asheville for 75 years and worked to achieve strides such as the election of Ruben Daley as the first Black member of Asheville City Council in 1969.

The center name also recognizes the Southside community, a large area that surrounds the center. Southside is a community of historically Black businesses, churches, and neighborhoods, some that remain and many which were demolished during Asheville’s urban renewal. In January, City Council approved a $6.7 million expansion of the Grant Southside Center to bring additional recreation and wellness opportunities to the neighborhood.

Stephens-Lee Community Center

Known as the Castle on the Hill, Stephens-Lee High School opened in 1923 and was for many decades western North Carolina’s only secondary school for Black students, drawing pupils from Buncombe, Henderson, Madison, Yancey, and Transylvania counties. An all-white school board closed the high school as part of its desegregation plan in 1965 and the entire multi-building campus, save for the gymnasium, was bulldozed in 1975.

Known as the Castle on the Hill, Stephens-Lee High School opened in 1923 and was for many decades western North Carolina’s only secondary school for Black students, drawing pupils from Buncombe, Henderson, Madison, Yancey, and Transylvania counties. An all-white school board closed the high school as part of its desegregation plan in 1965 and the entire multi-building campus, save for the gymnasium, was bulldozed in 1975.

Despite the many difficulties imposed by segregation, nearly all of Stephens-Lee’s faculty had master’s degrees with its education programs and extracurricular activities well-known throughout the southeast. The hyphenated name honors the legacy of George Henry Stephens, the first Black principal in Asheville (Catholic High School), and Hester Ford Lee, an educator and wife of Walter Smith Lee, the second principal of Catholic High School.

Check back next week for the histories behind Dr. George Washington Carver Edible Forest, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Park, Owens-Bell Park, and Herb Watts Park.