This entry is part of Park Views, an Asheville Parks & Recreation series that explores the history of the city’s public parks and community centers – and the mountain spirit that helped make them the unique spaces they are today. Read more from the series and follow APR on Facebook and Instagram for additional photos, upcoming events, and opportunities.

Like much of Asheville’s riverfront, Azalea Park can trace its history of recreation to ᏣᎳᎩ, romanized as Anigiduwagi and more commonly known as the Cherokee (ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ) people who built towns and villages along the Swannanoa River, complete with meeting plazas, hunting grounds, racetracks, and courts for ball play along riverbanks. It began its modern era as a much-loved public space as a 56-acre recreational lake and vital source of hydroelectric power.

Lake Craig and Recreation Park

In 1924, Hattie Whitson sold 260 acres adjacent to Asheville Tourist Camp to the City of Asheville for $5,000 with the explicit purpose of developing a lake and a hydroelectric plant, along with a provision that the land would revert to her heirs if it ceased to be used for public recreation. Asheville Tourist Camp was established by city government in 1921 on a site that originally served as a training camp for civilian women who worked for the Army during World War I, adding a dance floor and converting the former mess hall into a skating rink for enjoyment the next year.

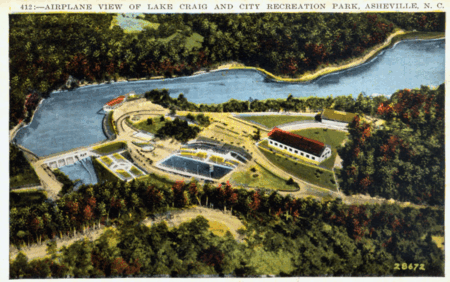

A concrete bridge and dam were built, using water from the Swannanoa River to create the scenic Lake Craig which was a major attraction when Recreation Park opened in 1925. The lake was named for Asheville resident and former North Carolina Governor Locke Craig. The tourist camp shuttered the next year and that area was converted to picnic grounds.

This new body of water quickly became a popular destination for boating, fishing, and other recreational activities. A series of small items were popular, particularly with young couples. In 1926, Recreation Park’s first swimming pool opened near the bridge, drawing water directly from the Swannanoa River. The area was also a summer retreat for notable figures including author Thomas Wolfe who stayed in a nearby cabin in 1937 to work on his novel Jack’s Last Party.

This new body of water quickly became a popular destination for boating, fishing, and other recreational activities. A series of small items were popular, particularly with young couples. In 1926, Recreation Park’s first swimming pool opened near the bridge, drawing water directly from the Swannanoa River. The area was also a summer retreat for notable figures including author Thomas Wolfe who stayed in a nearby cabin in 1937 to work on his novel Jack’s Last Party.

The lake’s glory was ultimately short-lived. Though it reportedly grew to cover 80 acres, it shrunk to 40 acres in 1944 when public health officials ordered its water lowered by 30 inches due to concerns about malaria. Throughout the 1940s, Recreation Park and Lake Craig were even closed on multiple occasions due to local polio epidemics.

Raising and lowering the lake’s water level increased sedimentation and heavy silt deposits and contributed to riverbank instability. Dredging was deemed too expensive, especially since the Swannanoa River’s flow was to be redirected to support to boost the city’s water supply when the North Fork Reservoir was created, further lowering the water level. Instead, the lake slowly disappeared until it could no longer be used for boating and swimming.

Decades of Uncertainty

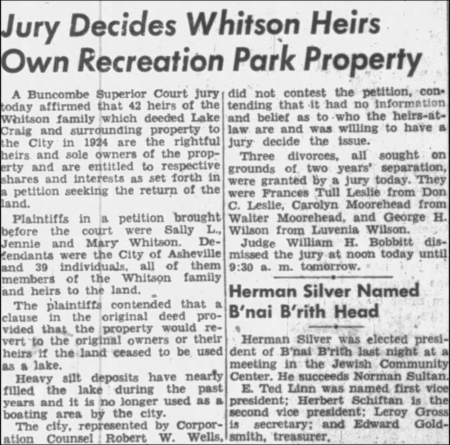

The lake’s decline culminated in 1951 when Hattie Whitson’s heirs filed a claim asserting the land was no longer being used for its intended recreational purpose and the land should be sold by a commission with proceeds divided among the family members. The following year, a Superior Court jury affirmed that the 42 heirs were the sole owners and the City did not contest the ruling.

The lake’s decline culminated in 1951 when Hattie Whitson’s heirs filed a claim asserting the land was no longer being used for its intended recreational purpose and the land should be sold by a commission with proceeds divided among the family members. The following year, a Superior Court jury affirmed that the 42 heirs were the sole owners and the City did not contest the ruling.

On the day before Easter, the lake was drained in just 90 minutes. The land that was once a hub of aquatic activity was converted to farmland, primarily used for growing corn. It also served as makeshift festival grounds and a weekend flea market on occasion. When Interstate 240 was built, much of the debris and stone was deposited on the southern banks of the Swannanoa River in this area.

While committees were formed in the late 1970s and early 1980s to explore the possibility of resurrecting the lake, those efforts never came to fruition. As a result of an agreement to combine water systems under the Asheville-Buncombe Water Authority, Recreation Park’s operations were transferred to Buncombe County in 1981.

Throughout the 1990s, City and County officials debated a plan to merge their recreation systems and build new sports fields on the old Lake Craig site. Community demand for fields even led to an unsuccessful proposal to sell Memorial Stadium to fund new field construction. In 1997, a feasibility study was commissioned to explore turning the property into a sports complex, but the idea was met with neighborhood pushback. Long used as an inert waste dump, Fawn Lake Reservoir was slated to become an overlook park and discussions began to transfer the dump’s operations to the Lake Craig site.

Rebirth of a Public Space

Rebirth of a Public Space

The push for new recreation facilities gained momentum in 1999 when an $18 million public bond referendum for parks and recreation improvements failed by a narrow margin of 357 votes, highlighting the community’s need for investment in its public spaces. This defeat spurred action and City Council unanimously approved the purchase of 155 acres on Azalea Road from the Moyer and Mabe estates for $18 million in 2001 including the former Lake Craig property. As one councilor remarked, it was frustrating that the City had once owned the land, only to abandon it and buy it back decades later.

The vision for a new park quickly took shape. Named in honor of a young soccer fan who tragically died in a car wreck, the John B. Lewis Soccer Complex was a central part of the plan. His family donated his life insurance money to help build the complex, fulfilling a wish he had expressed in a fifth-grade essay to “create spaces where children could play.”

With funding from the newly-established Tourism Product Development Fund and the North Carolina Parks and Recreation Trust Fund, construction began on the park. Major flooding in 2004 delayed construction, but Azalea Park opened in 2005 with synthetic turf soccer fields, a playground, restrooms, picnic shelters, and memorial gardens. A popular dog park was added in 2007.

With funding from the newly-established Tourism Product Development Fund and the North Carolina Parks and Recreation Trust Fund, construction began on the park. Major flooding in 2004 delayed construction, but Azalea Park opened in 2005 with synthetic turf soccer fields, a playground, restrooms, picnic shelters, and memorial gardens. A popular dog park was added in 2007.

The site’s transformation also included significant environmental work, with RiverLink establishing a conservation easement along the Swannanoa River and conducting stream restoration projects to prevent sediment pollution. In the process, general river water quality remains high within the park as evidenced by the classification of this portion of the river as hatchery-supported trout waters.

Following dissolution of the joint water authority, Recreation Park rejoined the Asheville Parks & Recreation (APR) system in 2005, but the two parks retained their individual names as they were separated by the Swannanoa River until a one-way connecting bridge was built in 2015 as part of a larger flood management, stormwater, and roadway improvement project that also saw the addition of a traffic light on Azalea Road and a water line providing drinkable water to the park and sports fields for the first time.

The Future of Azalea Park

A wooded trail system within the park has long been discussed, as well connections to Biltmore Avenue via the future Swannanoa River Greenway and to Morganton as part of the Fonta Flora State Trail. Providing access to more natural surface trails within city limits is a top priority of APR’s 10-year plan, Recreate Asheville, and the City of Asheville has entered into an agreement with AVL Unpaved Alliance to begin building and maintaining trails including a hilly multi-use trail near Thomas Wolfe Cabin in Azalea Park.

Tropical Storm Helene caused significant damage to Azalea Road, Gashes Creek Bridge, and the park itself in 2024, halting a recently-started visioning process to better connect contiguous municipal properties including WNC Nature Center, Recreation Park, and Azalea Park. However, the destruction left behind greater opportunities to transform the parks into well-planned recreation hubs that also support community resilience against natural disasters and protect neighborhoods and businesses located downstream. For more on Azalea Parks and Infrastructure Recovery, visit its official project page.

Tropical Storm Helene caused significant damage to Azalea Road, Gashes Creek Bridge, and the park itself in 2024, halting a recently-started visioning process to better connect contiguous municipal properties including WNC Nature Center, Recreation Park, and Azalea Park. However, the destruction left behind greater opportunities to transform the parks into well-planned recreation hubs that also support community resilience against natural disasters and protect neighborhoods and businesses located downstream. For more on Azalea Parks and Infrastructure Recovery, visit its official project page.

Do you have photos or stories to share about Azalea Park? Please send them to cbubenik@ashevillenc.gov so APR can be inspired by the past as we plan our future.

Photo and Image Credits

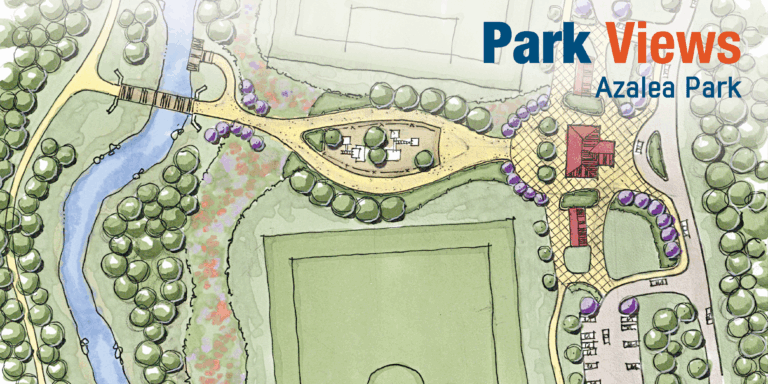

- An early planning image shows sports fields, memorial gardens, a playground, picnic shelters, concessions and restrooms building, parking, and a kayak launch.

- A colorized photo-offset postcard shows Lake Craig and Recreation Park in the 1920s. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

- Thomas Wolfe at work in Whitson’s cabin in the summer of 1937, sitting at a table with plenty of blank paper and an open carton of Chesterfield cigarettes. Print donated by Ewart Ball. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

- When the Lake Craig property reverted to the Whitson heirs, interests in the property ranged from 1-168th to one-eight, according to the Asheville Citizen newspaper.

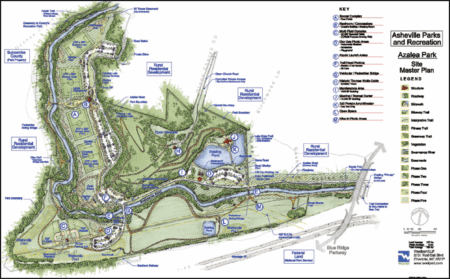

- The original Azalea Park site plan included several features that never materialized including a retreat center, diamond sports fields, disc golf, and a boardwalk.

- When Azalea Park was officially dedicated, Becky Lewis cut the ceremonial ribbon in the sports complex named for her son, John Lewis.

- Though the park has flooded multiple times since it opened – and serves to be intentionally flooded to protect homes and businesses downstream – Tropical Storm Helene caused catastrophic damage in 2024.

- One of the priority projects of AVL Unpaved Alliance is a hillside trail in Azalea Park.