This entry is part of Park Views, a weekly Asheville Parks & Recreation series that explores the history of the city’s public parks and community centers – and the mountain spirit that helped make them the unique spaces they are today. Read more from the series and follow APR on Facebook and Instagram for additional photos, upcoming events, and opportunities.

The 1970s marked a period of major expansion for Asheville’s public recreation options as federal and state grants brought new parks and community centers to neighborhoods throughout the city. After many years of work, Tempie Avery Montford Community Center opened as the city’s first full-complex recreation space that was built from the ground up, becoming a social and cultural hub for the Montford, Stumptown, and Hill Street neighborhoods.

Tempie Avery

State Senator Nicholas Woodfin purchased Tempie Avery in 1840 while he and his new bride Eliza honeymooned in Charleston, South Carolina. Avery would start her life on the Woodfin plantation helping raise the couple’s three daughters in service as a handmaiden and late become the family’s beloved nurse.

State Senator Nicholas Woodfin purchased Tempie Avery in 1840 while he and his new bride Eliza honeymooned in Charleston, South Carolina. Avery would start her life on the Woodfin plantation helping raise the couple’s three daughters in service as a handmaiden and late become the family’s beloved nurse.

Following emancipation, her former slave masters gave a valuable tract of land on Pearson Drive to Avery and she worked as a nurse and midwife. Her descendants would live on the same land for nearly 100 years as a Black neighborhood named Stumptown developed around them with homes, churches, and stores.

Many of Avery’s life details are unknown. She married Silas Haynes around 1850 (unofficially, as enslaved unions were not legally recognized until 1866) and then married Riley Avery around 1861 after her first husband reportedly fled to freedom. She had nine known children. When she passed away in 1917, she was buried at Riverside Cemetery. Avery’s death certificate lists her birth as April 1817 in Morganton, North Carolina to unknown parents.

Avery’s contributions to Asheville went beyond her devotion and service to the Woodfins and her own family. Newspaper clippings during and after her lifetime show she was an esteemed local figure who would “brighten up at the prospect of telling about the incidents of her life, and it was only necessary to ask a new question every little while to reopen the floodgates of memory.”

Stumptown

The historic boundaries of Stumptown are roughly 30 acres within the location of today’s Birch and Jersey streets on the north and south, Pearson Drive on the east, and Riverside Cemetary on the west. The Hill Street neighborhood developed adjacent to Stumptown, and a school and a hospital for Black residents opened there in the early 20th century. In the 1930s, both areas were redlined, a discriminatory banking practice that denied Black people’s access to financing.

The historic boundaries of Stumptown are roughly 30 acres within the location of today’s Birch and Jersey streets on the north and south, Pearson Drive on the east, and Riverside Cemetary on the west. The Hill Street neighborhood developed adjacent to Stumptown, and a school and a hospital for Black residents opened there in the early 20th century. In the 1930s, both areas were redlined, a discriminatory banking practice that denied Black people’s access to financing.

According to the Asheville African American Heritage Resource Survey, residents remember Stumptown as tight-knit and familial, where children were watched over by everyone. Community life centered on neighborhood institutions including Mr. Howard’s Sweet Shop, Midget Ice Cream Parlor, and Welfare Baptist Church.

Residents advocated for a public park as early as the 1950s, but eventually took matters into their own hands. In 1968, Stumptown Neighborhood Center opened in a house next to the church. The small community center served about 40 children with just a ping pong table, television, record player, cards, one horse shoe set, checkers, coloring books, and puzzles.

Phyllis Sherrill, Co-Chair of the Model Cities Physical Environment and Transportation Task Force, organized a campaign around the same time calling on the City of Asheville to remove abandoned cars blocking Stumptown streets (some that were made of dirt or gravel) and build a small playground next to the community center. Sherrill’s campaign brought attention to decades of insufficient government investment in streets and sidewalks, water and sanitation systems, and other city services.

Phyllis Sherrill, Co-Chair of the Model Cities Physical Environment and Transportation Task Force, organized a campaign around the same time calling on the City of Asheville to remove abandoned cars blocking Stumptown streets (some that were made of dirt or gravel) and build a small playground next to the community center. Sherrill’s campaign brought attention to decades of insufficient government investment in streets and sidewalks, water and sanitation systems, and other city services.

While a 1970s Stumptown appraisal report lists “several nice homes,” it also points out most did not meet building and zoning code requirements. The report also notes, “Interviews with residents of the neighborhood convinced this appraiser that there are some fine people living in Stumptown. Many of these people went out of their way to show me where homes or churches had stood in former years. Many of the residents take great pride in their modest homes and are proud of their vegetable gardens and flowers.”

Asheville’s Model Cities program began planning a park for the area in 1970. Two years later, City Council unanimously approved the plan for Riverside Park presented by Dr. Oralene Simmons, an elected Model Cities commissioner who chaired the committee that drafted the plan. Included were a ballfield, tennis courts, parking lots, basketball court, restrooms, playgrounds, picnic shelter, and wading pool.

Over the next decade, the plan for Riverside Park saw multiple revisions. While at least 250 families lived in Stumptown in the 1930s, it had dwindled to around 80 households by the time officials began acquiring land for the new park. Due to the nature of redlining, some homes had been abandoned or turned into low-price rentals when costs of repairs could not be justified by their owners, many older and no longer able to work. Many lots had been subdivided between family members and others were vacant, so locating owners was a slow process.

Eventually, park space was obtained by negotiation with property owners or through condemnation. The neighborhood largely disappeared with residents moving out of the city or to other parts of Asheville, though multiple Stumptown reunions have taken place over the years. A small cluster of streets survives on the north end of the neighborhood.

Montford Recreation Center

As new grants were paired to match funds from federal urban renewal programs, Riverside Park (using Model Cities funds) grew to include a community recreation center (using Community Development Block Grant Funds), then an additional five acres connecting the two spaces and adding tennis courts, a larger playground, and 50-meter swimming pool (using U.S. Housing and Urban Development funds). City of Asheville also committed to repaving and widening streets, installing sidewalks, and rehabilitation of existing homes.

The recreation center opened in 1978 with an auditorium-gymnasium that included locker rooms, craft and game rooms, offices, and a kitchen. Simmons, who presented the original Riverside Park plan to City Council, served as the center’s assistant director. It immediately became the heart of the entire neighborhood with daily programs, activities, clubs, and meetings focused on young people, teens, and older adults.

The recreation center opened in 1978 with an auditorium-gymnasium that included locker rooms, craft and game rooms, offices, and a kitchen. Simmons, who presented the original Riverside Park plan to City Council, served as the center’s assistant director. It immediately became the heart of the entire neighborhood with daily programs, activities, clubs, and meetings focused on young people, teens, and older adults.

However, some compromises had been made. Officials determined an access road from Courtland Avenue to better connected residents of Hillcrest Apartments would be too costly. City Council also cited annual operating costs when scrapping a proposed swimming pool that had been requested by Montford Community Club and Asheville Parks & Recreation (APR). Using Model Cities funding to match a federal grant, the pool would have not impacted the construction budget. Councilor Gene Rainey was the only member to vote for the pool, predicting “never again will an opportunity like this come along.”

Naming the center proved somewhat controversial. Some argued it should be named for a prominent leader in the Montford community. Stumptown’s development predates that of Montford, a separate neighborhood that initially included homes of white businessmen who were primarily lawyers, doctors, and architects, but became one of Asheville’s most integrated areas by the 1970s. When part of Montford was designated as an Historic District and listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1977, it did not include Stumptown or Hill Street. The building opened as Montford Recreation Center, but City Council unanimously approved renaming the facility Tempie Avery Montford Center in 2017.

Naming the center proved somewhat controversial. Some argued it should be named for a prominent leader in the Montford community. Stumptown’s development predates that of Montford, a separate neighborhood that initially included homes of white businessmen who were primarily lawyers, doctors, and architects, but became one of Asheville’s most integrated areas by the 1970s. When part of Montford was designated as an Historic District and listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1977, it did not include Stumptown or Hill Street. The building opened as Montford Recreation Center, but City Council unanimously approved renaming the facility Tempie Avery Montford Center in 2017.

Riverside Park

Even though planning for the park began before planning for the community center, outdoor recreation areas were not completed until the early 1980s. These included tennis courts, a basketball court and playground, picnic areas and benches, natural wooded areas, and multi-use field for baseball, softball, and football with concession stand and restrooms. Officially referred to as Riverside Park, it was also known locally as Montford Recreation Park, Stumptown Park, or, simply, Montford Center or Montford Complex.

Even though planning for the park began before planning for the community center, outdoor recreation areas were not completed until the early 1980s. These included tennis courts, a basketball court and playground, picnic areas and benches, natural wooded areas, and multi-use field for baseball, softball, and football with concession stand and restrooms. Officially referred to as Riverside Park, it was also known locally as Montford Recreation Park, Stumptown Park, or, simply, Montford Center or Montford Complex.

Simmons had been promoted to director of the center by 1982 when she recruited Sherrill and others to host a prayer breakfast celebrating the vision of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The first Keep the Dream Alive Prayer Breakfast grew from about 100 attendees on a snowy day to more than 400 the next year. The Martin Luther King Jr. Association of Asheville and Buncombe County operated under the auspices of APR until 2003 when it became an independent nonprofit organization. Its work now includes the prayer breakfast, peace march and rally, scholarship and community service awards, and additional programs throughout the year.

In 1983, an amphitheater opened in a part of the park that had been known as The Hollow when it was Stumptown. Montford Park Players (MPP) got its start – and its name – when its first shows were performed in nearby Montford Park. After relocating to City-County Plaza (now Pack Square Park), MPP moved to the new amphitheater, a residency that continues today. MPP serves as North Carolina’s longest running Shakespeare theater company and City Council unanimously approved renaming the performance space to Hazel Robinson Amphitheater in honor of the company’s founder in 1997.

In 1983, an amphitheater opened in a part of the park that had been known as The Hollow when it was Stumptown. Montford Park Players (MPP) got its start – and its name – when its first shows were performed in nearby Montford Park. After relocating to City-County Plaza (now Pack Square Park), MPP moved to the new amphitheater, a residency that continues today. MPP serves as North Carolina’s longest running Shakespeare theater company and City Council unanimously approved renaming the performance space to Hazel Robinson Amphitheater in honor of the company’s founder in 1997.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the center hosted lectures, dinner theater, aerobics, ceramics classes, senior meals, APR Afterschool, and more in addition to annual special events such as Miss Montford and Prince of Montford pageants, Ethnic Exchange Festival, and Outdoor Gospel Festival. Proving the connection to the community extended beyond the boundaries of the recreation complex, APR staff coordinated neighborhood holiday decorating contests and helped plan Montford Music and Arts Festival in its earliest years.

Entering the New Millenium

Although the community center and park continued to be used and enjoyed by the neighborhood, they were in need of improvements to match the quality of their activities and events. APR’s adventure programs joined the community center when a 20-foot indoor climbing wall was installed.

Although the community center and park continued to be used and enjoyed by the neighborhood, they were in need of improvements to match the quality of their activities and events. APR’s adventure programs joined the community center when a 20-foot indoor climbing wall was installed.

An unrealized 2005 plan called for walking trails, outdoor ropes courses, accessibility upgrades, playground replacement, amphitheater enhancements, street widening at the entrance, and artistic markers celebrating Stumptown. Many of these features were incorporated into a 2015 master plan. Following overwhelming support from Asheville voters for a bond referendum supporting parks and recreation facilities improvements, the first phase of the master plan was completed with greatly expanded parking, accessible walkways and playground surfacing, expanded natural areas, and a new playground, basketball and bocce courts, outdoor classroom, sitting areas with long-range views of mountain vistas, and table tennis plaza.

For more on Stumptown, Hill Street, and Black roots in Asheville, read the Asheville African American Heritage Resource Survey.

Do you have photos or stories to share about Tempie Avery Montford Community Center? Please send them to cbubenik@ashevillenc.gov so APR can be inspired by the past as we plan our future.

Photo and Image Credits

- While the building maintains much of the functional and minimalist charm associated with late-1970s government buildings, recent enhancements emphasize the natural beauty of the park with views of the Blue Ridge Mountains and the distinctive architecture of nearby Montford houses.

- Temperance Avery, better known as Tempie (sometimes written Tempy or Tempe), was a beloved Ashevillian known for her affection for children and telling detailed anecdotes about her life. Following her emancipation, she used her skills as a nurse and midwife out of her home to support herself and her children. In this 1897 photo, Avery holds Pauline Moore. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

- It is difficult to locate accurate historical sources of early Black life in Asheville, though multiple groups and individuals are working to chronicle and preserve that history. Most accounts place Stumptown as an established community by 1880, which is supported by this 1891 map showing a cluster of houses in that area with the future location of Montford largely undeveloped. Montford incorporated as an independent town in 1893 before its real estate company went bankrupt. It was rescued a year later by George Willis Pack (who made Montford profitable and donated land for Aston, Magnolia, and Pack Square parks) and annexed into Asheville in 1905. This 1912 map indicates an expanded Stumptown and development of Montford with Pearson Drive acting as a “color line.” By the time the community center and park opened, Montford was one of the most racially integrated neighborhoods in Asheville. Fowler, T. M. & Charles Hart Litho. (1912) Asheville, Buncombe Co. N. Passaic, N.J. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/75694896.

- As physician Dr. Mary Frances Shuford grew to know renters of houses she owned in Stumptown, she realized that public agencies were failing low income neighborhoods. In the 1940s, she campaigned to establish a hospital for Black residents on Biltmore Avenue, provided medical care to the neighborhood, and served as Stumptown’s demonstration kindergarten teacher at Welfare Baptist Church in Stumptown starting in 1962. She converted one of the homes she owned on 8 Madison Street into Stumptown Neighborhood Center with help from community action groups. A lot next to the house had become an unofficial junk yard and it took 10 days to remove all of the trash. Plans for the site included a greenhouse, playground, and conversion of a vacant lot known as Smathers Woods (owned by he City of Asheville) from a swamp into a park. Staff photo by Bert Shipman, 1967. Courtesy of Asheville Citizen Times.

- The groundbreaking ceremony for Tempie Avery Montford Center included elbow grease from organizers including Mrs. Wakefield, Simmons, Mayor Eugene Ochsenreiter, Montford Community Club President Bob Pitts, and others. Simmons was a longtime APR team member who served as director of Tempie Avery Montford Center and Cultural Arts Supervisor. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

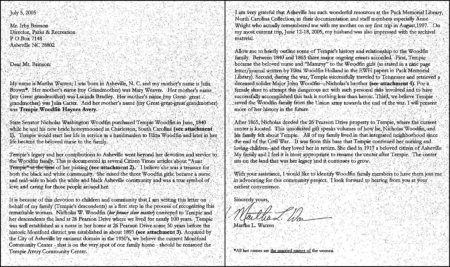

- Avery’s great-great-great-great-granddaughter Marth Warren wrote APR in 2005 advocating to rename the community center. She included articles and research she completed using Buncombe County Special Collections archives.

- When Martin Luther King Jr. Day became a federally observed holiday in 1986, the organizers of the local prayer breakfast decided to invite Shirley Chisholm to provide the keynote address. The event was moved from the community center to Asheville Civic Center to accommodate more than 2,000 attendees. Chisholm was the first Black woman elected to congress and the first woman and African American to seek the nomination for president of the United States from one of the two major political parties. Pictured with Simmons (center) and Sherrill (right), Chisholm borrowed clothes and shoes from Simmons’ friends when her airline lost her luggage. Asheville’s annual Prayer Breakfast continues today as one of the largest and most admired MLK celebrations in the southeast. Courtesy of The Martin Luther King Jr. Association of Asheville and Buncombe County.

- Montford Park Players have presented free Shakespeare and other classic plays at Tempie Avery Montford Center’s Hazel Robinson Amphitheatre since it opened in 1983. In this production, Othello (Rocky Fulp, standing) addresses the Venetian Senate. Marshall Gates (center) and either Stephen or Peter Whelihan appear as senators. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

- Tempie Avery Montford Center’s indoor climbing wall offers instructional courses, glow-in-the-dark events, and climbing clubs for all ages.

- The park’s updated playground features an inclusive design and serves as a space for kids, teens, and adults to explore, connect, and discover.